The Sack of Baghdad and the Slow Death of a Knowledge Civilization

Introduction: Destruction Is Loud, Loss Is Silent

History often remembers destruction in dramatic images. Burning cities. Fallen walls. Mass death. But the deepest damage happens quietly, long after the noise fades. The Sack of Baghdad in 1258 was one of those moments. It did not only destroy a city. It erased continuity.

Baghdad was not just an Abbasid capital. It was a living archive of human effort. Generations of scholars had worked there, correcting texts, debating ideas, and passing knowledge forward. When the city fell, that chain was broken. What followed was not just political collapse, but a long intellectual silence.

1. Baghdad as a Living Knowledge System

Before its fall, Baghdad functioned as an integrated knowledge system. Scholars were not isolated figures working alone. They were part of networks that included teachers, students, scribes, librarians, and patrons. Knowledge moved through conversation, debate, and handwritten transmission.

Libraries were not static buildings filled with books. They were active spaces where texts were copied, compared, and improved. Errors were discussed openly. Marginal notes carried generations of commentary. Baghdad’s strength lay in this constant motion of ideas.

This system depended on stability. When that stability collapsed, the system collapsed with it.

2. Political Weakness Before the Invasion

The Abbasid Caliphate had been weakening for decades before the Mongols arrived. Authority was fragmented. Military power was divided. Court politics distracted leaders from external threats. Scholars continued their work, but the political structure protecting them was fragile.

This separation between intellectual vitality and political weakness created a dangerous illusion. Baghdad still felt strong because learning continued. But power no longer existed to defend that learning.

History often shows this pattern. Intellectual life can survive political decay for a time, but not indefinitely.

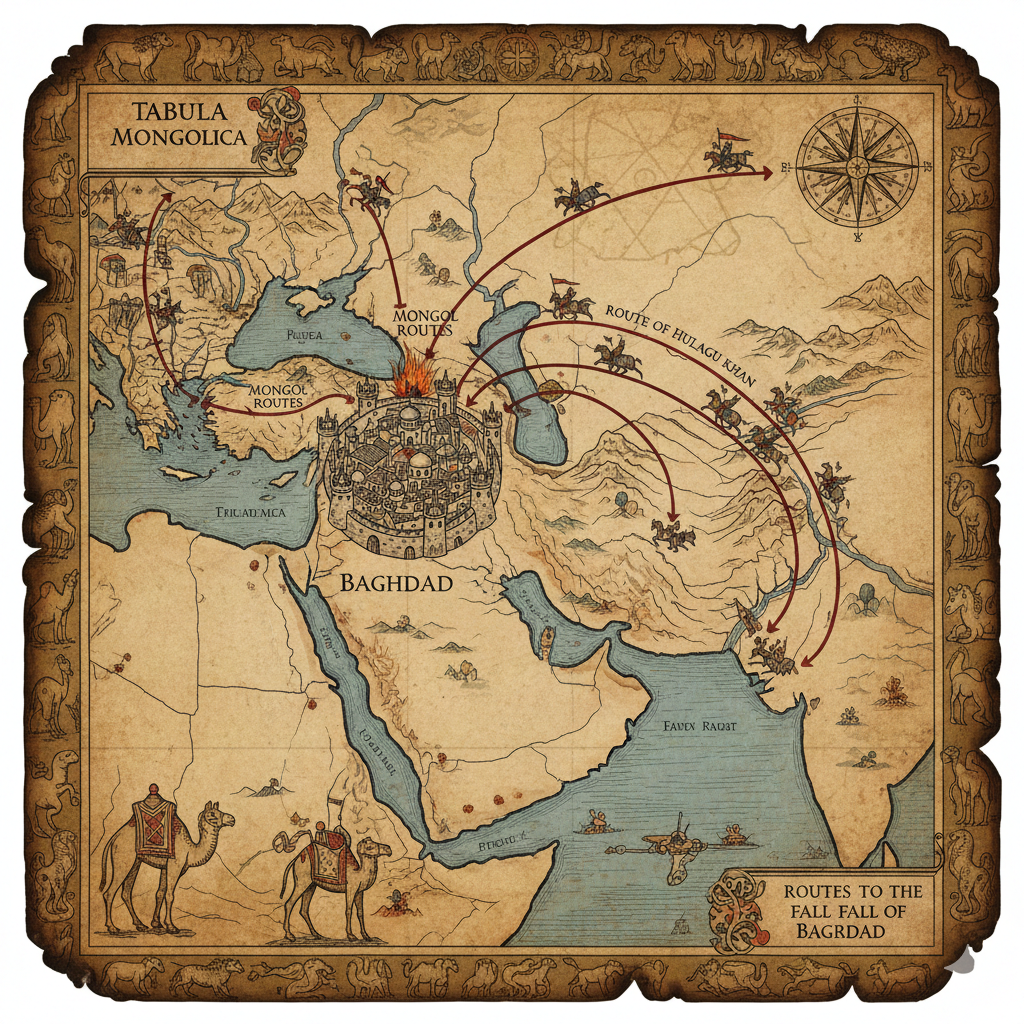

3. The Mongols and a New Kind of War

The Mongols were unlike previous invaders. They did not seek assimilation or gradual control. Their strategy relied on terror, speed, and total destruction. Cities were given a choice: surrender or disappear.

Baghdad underestimated this threat. Negotiation was attempted where preparation was needed. Defensive planning was weak. Internal divisions slowed decision-making. When the Mongols arrived, the city was psychologically unprepared for the scale of violence that followed.

The fall was swift, but the consequences were permanent.

4. The Siege and Collapse

Once the siege began, Baghdad’s defenses failed quickly. Flooded areas, broken walls, and confused leadership accelerated collapse. Resistance was brief and ineffective.

After the city fell, order vanished. Mongol forces moved through neighborhoods without restraint. There was no distinction between soldier and civilian, scholar and laborer. The logic was simple. Destroy everything that could sustain resistance or memory.

This was not conquest in the traditional sense. It was erasure.

5. Libraries as Targets, Not Accidents

The destruction of libraries was not accidental. Libraries represented continuity, identity, and intellectual power. Destroying them ensured that recovery would be slow, if not impossible.

Manuscripts were burned, torn, or thrown into rivers. These were not symbolic losses. Each manuscript represented years of labor. Many were unique copies. Some contained corrections and discussions never recorded elsewhere.

When these books disappeared, entire conversations disappeared with them.

6. Scholars Without Students

Even those scholars who survived faced a different loss. Their students were gone. Their libraries were destroyed. Their communities were scattered. Knowledge requires transmission. Without students, scholars become the last holders of information.

Many fled to other regions. Others abandoned scholarship entirely. The chain of learning broke not because minds were lost, but because the environment that supported learning no longer existed.

This is how civilizations forget.

7. The End of Abbasid Patronage

The Abbasid Caliphate had long served as a patron of learning. Even during political decline, its institutions provided salaries, protection, and legitimacy to scholars.

With the caliph’s execution, that system vanished. No central authority replaced it. Scholarship became localized, fragmented, and cautious. Large-scale projects disappeared. Long-term preservation became impossible.

Knowledge survived in fragments, not as a unified tradition.

8. Psychological Impact on the Muslim World

The Sack of Baghdad shattered confidence across the Muslim world. Baghdad had symbolized continuity with the Prophet’s community, scholarly authority, and civilizational leadership. Its destruction created a psychological rupture.

Communities turned inward. Intellectual ambition narrowed. Survival replaced expansion. The loss was not only material. It was emotional and cultural.

Fear is not fertile ground for scholarship.

9. Why Recovery Never Fully Happened

Some cities recover after devastation. Baghdad did not reclaim its former role. The reasons are clear:

- Repeated invasions prevented stability

- Scholars dispersed permanently

- Libraries were not rebuilt at scale

- Patronage systems never returned

Once a knowledge ecosystem collapses, rebuilding it requires generations. Baghdad never received that uninterrupted time.

10. Global Loss Beyond Islamic Civilization

The destruction of Baghdad was a loss for humanity as a whole. Many works preserved there were translations of ancient Greek, Persian, and Indian texts that no longer existed elsewhere.

Modern historians often forget that what survives today is only a fraction of what once existed. The Sack of Baghdad created permanent gaps in human understanding. Entire scientific and philosophical traditions may have vanished without trace.

Silence is the hardest loss to measure.

11. Patterns Repeated in History

The fall of Baghdad fits a recurring historical pattern. Civilizations that neglect protection of knowledge eventually lose both culture and power. Armies defend borders, but libraries defend memory.

When leaders fail to understand this, destruction becomes irreversible.

Conclusion: When Memory Is Destroyed

The Sack of Baghdad was not the end of Islam or Muslim scholarship. But it marked the end of a world where knowledge was organized, protected, and central to power.

What was lost cannot be fully recovered. What remains is a lesson written in absence. Civilizations survive not because they build monuments, but because they preserve memory.

When books die, civilizations grow silent.

References & Sources

- Ibn Kathir, Al-Bidaya wa al-Nihaya

- Ibn Athir, Al-Kamil fi al-Tarikh

- Ata Malik Juvayni, History of the World Conqueror

- Hugh Kennedy, The Mongols and the Islamic World

- David Morgan, The Mongols

- Marshall Hodgson, The Venture of Islam